Personal Wealth Management / Economics

2018 Doesn’t Prove Rate Hikes Are Bad for Stocks

2018’s late-year stock market correction had another cause, in our view.

Buckle up! That largely sums up the reaction of many financial commentators we follow to the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed’s) decision Wednesday to reduce its quantitative easing (QE) asset purchases faster than initially planned, reducing monthly purchases by $30 billion (£22.6 billion) instead of $15 billion (£11.3 billion). The Fed’s statement also set expectations for “similar” monthly reductions from here, a path to ending QE in March—which many presume would tee up a fed-funds target rate hike in 2022’s first half. We also saw ample chatter about the so-called dot plot of Fed members’ forecasts, showing they collectively project three rate hikes in the year (based on the economic conditions they anticipate, which we think is hardly etched in stone). That, rather than QE’s impending end, has preoccupied most Fed coverage we have seen over the past couple of weeks, with many commentators blaming 2018’s stock market decline on that year’s Fed hikes. Whilst we (nor anyone) can’t predict Fed policy from here, we can correct the record on 2018, which we think had very little to do with the Fed.

As best we can tell, the theory that rate hikes drove 2018’s negativity rests on two observations: The Fed hiked rates throughout the year, and its last increase—on 19 December—roughly coincided with the S&P 500’s Christmas Eve low and global markets’ Christmas nadir.[i] Yet zeroing in on those facts is a bit too selective, in our view. Consider: The Fed started its rate hike cycle way back in December 2015. The S&P 500 did fine in 2016, rising 12.0% in USD.[ii] Global shares returned an even better 28.2% in GBP.[iii] The next rate hike arrived that December, and three more followed in 2017. Stocks’ party continued, with the S&P 500’s 21.8% return in USD and global stocks’ 11.8% in GBP defying rate hike fears.[iv]

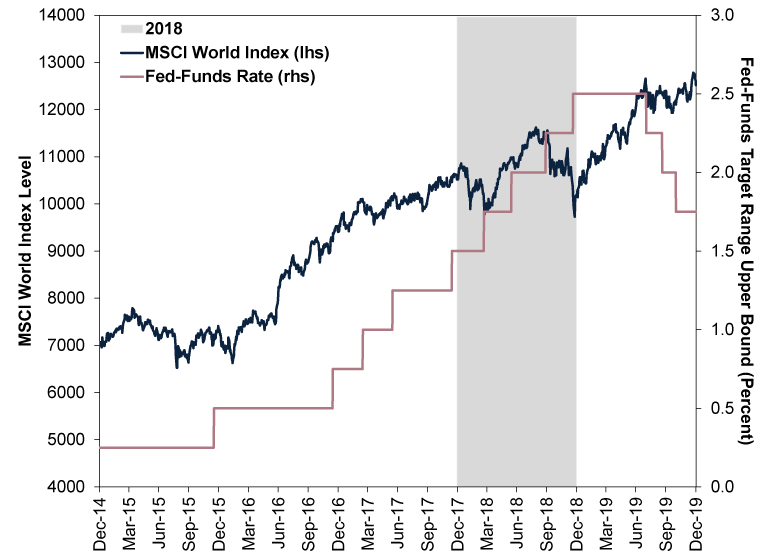

Even in 2018, stocks’ woes didn’t align with the Fed’s moves. As Exhibit 1 shows, whilst global markets’ full-year returns were negative in a year the Fed hiked four times, that negativity was concentrated in the autumn. After suffering a brief correction (a sharp, sentiment-fuelled move of around -10% to -20%) in the winter, the MSCI World Index climbed through spring and summer and hit the year’s high point in late August, enduring another rate hike along the way. In our view, saying the Fed’s decision to raise rates twice in the autumn, for a total 0.5 percentage point increase, caused the MSCI World’s -16.3% decline from that 28 August through Christmas strains credulity.[v]

Exhibit 1: Stocks Mostly Didn’t Mind Rate Hikes in 2018

Source: FactSet, as of 31/12/2021. Fed-Funds Target Range Upper Bound and MSCI World Index return in GBP with net dividends, 31/12/2014 – 31/12/2019.

In our view, rate hikes were coincidental to stocks’ late-2018 volatility. The deep correction’s proximate cause, based on our research, was a wave of late-year selling by hedge funds—some that were liquidating holdings to prepare for closure, and some that were raising heaps of cash in anticipation of a flood of redemption requests. In both cases, we think the culprit was years of poor performance, which resulted in restless shareholders and low revenues under hedge funds’ typical “2 & 20” fee model (charging 2% of assets under management plus 20% of excess returns). Under the 2 & 20 model, performance often doesn’t reset annually, so after a spell of disappointing returns, funds generally must recoup prior lag before collecting that 20% on excess returns. That means a string of disappointing years can wreck revenues, potentially making it prohibitively expensive for some funds to keep operating. For many fund managers, we think it can become easier to fold and start over than try to keep going in hopes of eventually earning that fee for outperforming.

Hedge fund data is notoriously difficult to come by, as the industry is largely opaque and unregulated in America. But based on the media’s reporting at the time, our interactions with market makers and our experience, we think scores of hedge funds were in this predicament as 2018 drew to a close. By all indications in financial publications we follow, hedge funds’ performance was quite dreary in the middle of the last decade. We are also aware that many managers were pessimistic on stocks after former US President Trump won 2016’s election. Those who reduced stock exposure accordingly could have missed the bulk of global stocks’ 16.5% return between Election Day 2016 and 2017’s end.[vi] If they flipped to being optimistic on stocks for 2018 and repositioned accordingly, they then got hit by stocks’ twin corrections, possibly leaving them down on the year by early December based on the market movement depicted in Exhibit 1. Those who decided to close then had to liquidate holdings in a hurry. Those who remained open were staring down pre-determined redemption windows, and we think they anticipated clients fleeing in January 2019 and decided to raise cash. (Most hedge funds allow shareholders to cash in or redeem their holdings in pre-determined windows.)

As fund managers sold indiscriminately, appearing to cause big daily plunges in December, we think it spooked investors broadly, leading to a broad, sentiment-driven selloff—a correction. Late-year rate hikes, in our view, were merely unrelated window dressing.

Rate hikes aren’t inherently bearish, in our view. Like every monetary policy decision, we think whether they are a net benefit or detriment depends on market and economic conditions at the time, including how they affect the risk of a deep, prolonged, global yield curve inversion. (The yield curve is a visual representation of interest rates across the spectrum of maturities, and it is inverted when short rates exceed long rates. Our research shows a deep inversion is a negative forward-looking economic indicator.) 2018’s rate hikes flattened the US yield curve, but they didn’t invert it.[vii] Right now, with a roughly 1.4 percentage-point gap between 3-month and 10-year US Treasury yields, an incremental Fed rate hike looks unlikely to cause big trouble.[viii] Maybe that changes by the time the Fed acts, but that isn’t knowable now. Hence, rather than sweat what the Fed might do months in advance, we think it is best to just wait and see and weigh monetary policy decisions after the fact.

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 15/12/2031. Statement based on S&P 500 total return in USD and MSCI World Index in GBP. Currency fluctuations between the dollar and pound may result in higher or lower investment returns.

[ii] Ibid.. S&P 500 total return in USD, 31/12/2015 – 31/12/2016. Currency fluctuations between the dollar and pound may result in higher or lower investment returns.

[iii] Ibid. MSCI World Index return in GBP with net dividends, 31/12/2015 – 31/12/2016.

[iv] Ibid. S&P 500 total return in USD and MSCI World Index return in GBP with net dividends, 31/12/2016 – 31/12/2017. Currency fluctuations between the dollar and pound may result in higher or lower investment returns.

[v] Ibid. MSCI World Index return in GBP with net dividends, 28/8/2018 – 25/12/2018.

[vi] Ibid. S MSCI World Index return in GBP with net dividends, 8/11/2016 – 31/12/2017.

[vii] Based on data from FactSet, there was an inversion about six months after the Fed’s last hike, starting in May 2019. But stocks had already rebounded from December’s correction by then, as Exhibit 1 showed, and the inversion was too shallow to have had much effect, in our view.

[viii] Source: FactSet, as of 15/12/2021.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights.

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

See Our Investment Guides

The world of investing can seem like a giant maze. Fisher Investments UK has developed several informational and educational guides tackling a variety of investing topics.