Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

On Inflation, Trust the Market

No indicator is perfect, but the market is right a lot more often than the zeitgeist.

Ouch. That about sums up the collective reaction to the news that December’s US CPI inflation rate hit 7.0% y/y—the fastest rate since 1982.[i] Considering the inflation rate a year prior was just 1.4%, the sharp acceleration has jarred many households and businesses, which are wrestling with higher costs.[ii] But if you were invested in stocks over the past year, it is worth noting your investments probably provided a nice hedge, as global markets rose much faster than consumer prices. In our view, this is critical to remember as inflation continues topping the list of investors’ fears in 2022.

US inflation has morphed into a hot button political issue in recent months, with people on both sides of the aisle trying to spin it to their advantage. Even the discussion of its causes has become hotly politicized. So please understand that when we discuss inflation and its stock market implications, we aren’t making ideological or political statements. This isn’t even about whether faster inflation is good or bad—obviously, if prices rise 7% in a year and make it harder for people and small businesses to make ends meet, that isn’t good. Yet at times like this, it is crucial to think about events and risks as markets do. Stocks don’t view things in terms of “good” or “bad” in the absolute sense. That debate is squarely in the human, societal realm. For stocks, the question is at once more simple and more complex: Is there any material trouble left that markets haven’t already priced in? Is there any negative surprise power left? A strong likelihood of a bad outcome that investors haven’t already considered?

That last question is the linchpin, in our view. It is almost cliché to say markets are efficient and forward-looking, so please don’t get annoyed with us for going there. But overwhelmingly, we have found that in any sufficiently liquid market, be it stocks, bonds or what have you, prices reflect all widely known information at any given time. “Information” includes facts, figures and data. It also includes interpretations of those facts, figures and data, and the hopes and fears that emerge from that analysis. And it includes forecasts, which are really just opinions on how said facts, figures and data will evolve in the future—and, perhaps, what that evolution will mean for asset prices.

Now, no one can prove this scientifically, beyond a shadow of a doubt. But simple logic and reason can get us close enough: People buy and sell constantly, with heads full of knowledge, viewpoints, biases and forecasts. Since last April, when the BLS announced the CPI inflation rate crossed above 2.0% for the first time in a while, investors have bought and sold stocks and bonds with full knowledge of inflation’s acceleration. In more recent months, supply chain issues have loomed large in the market’s hive mind, as has the Fed’s decision to stop using the word “transitory” to describe accelerating inflation—a shift we still think was an attempt to be more clear, but which most interpreted as a public confession that the Fed’s earlier views were wrong. Thus the prospect of inflation staying higher for longer became the dominant view. Now the end of quantitative easing (QE) asset purchases looms large, as do potential short-term interest rate hikes. All of which people generally view quite negatively. This pessimism has played into the purchase or sale prices that so many investors have decided to accept, whether consciously or not. Therefore, we can reason that these fears are all reflected in prices, also known as being “priced in.”

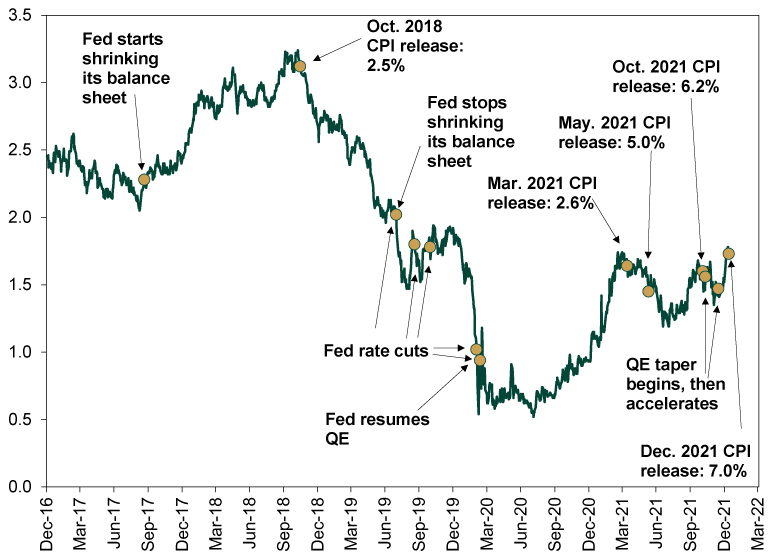

Stocks move on political as well as economic drivers, so some will argue there are too many confounding variables to use stocks’ big 2021 as a counterpoint to inflation fears. The counterfactual—how stocks would be faring if inflation were milder—is also unknowable. But bonds have a more direct relationship with inflation, which erodes the future value of fixed interest payments as well as the bond’s face value at maturity. So in general, the higher the expected inflation rate, the higher the interest rate investors will charge to preserve purchasing power. If inflation were likely to stay high enough for long enough to cause big problems, we should see it in elevated long-term Treasury yields. Yet, much as everyone is hyping the new year’s recent yield climb, as Exhibit 1 shows, the 10-year Treasury yield hasn’t jumped alongside the inflation rate. It actually fell for a good four months as the inflation rate accelerated past 5.0%. Following a brief uptick, it fell again as the Fed started reining in QE, a development everyone thought would bring higher rates. Even with the recent uptick, today’s 1.73% 10-year yield is right around where it was in late March, when the inflation rate was much, much lower.

Exhibit 1: 10-Year US Treasury Yield, the Fed and Inflation

Source: FactSet, as of 1/12/2022. 10-year US Treasury yield (constant maturity), 12/31/2016 – 1/12/2022.

The market knows inflation hit 7.0% last month, and it likely priced that outcome well before today’s data confirmed it. It knows people worry about the implications. It knows that one political party is blaming corporate greed while the other party is blaming its opponent’s spending plans. Yet it also knows that the culprit most apparent in the data—the supply chain crisis—is starting to ease up. It knows people surveyed in December purchasing managers’ indexes across the US and Europe reported cost and logistics pressures are starting to moderate. It has seen numerous businesses’ investments in increased capacity. It has seen the push toward vertical integration that larger companies are using in hopes of controlling their costs and destiny. And it has seen the inflation math evolve over the past year, so it knows that in a few months, lockdown-deflated early-2021 prices will be out of the denominator in the year-over-year calculation, removing the funky math helping skew the inflation rate higher. It has seen all of this and, based on where yields are, it has decided inflation isn’t a major problem for stocks. This, coming from the most efficient pricing and forecasting mechanism on earth.

Yes, markets can be inefficient in the short-term—this is where corrections and bubbles alike come from. But it isn’t in markets’ nature to ignore something as big as inflation for over half a year. So, in our view, the most rational conclusion when the hype says one thing and the market says another is that the market is right. If it knows where inflation is and how people and businesses are responding to it and long-term yields aren’t soaring, that is a powerful signal. Take a deep breath, and trust it.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.