Personal Wealth Management / Behavioral Finance

Reflecting on Kahneman’s Lessons

A tribute to Daniel Kahneman’s lasting impact on how we think about financial decisions, using one of his greatest lessons.

The world lost a titanic figure in the field of behavioral economics and finance Wednesday, as Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel-prize winning economist, passed away at 90. He leaves us a rich legacy exploring how people’s cognitive biases affect their decisions. And in that vein, we bring you a variation on one of his most famous experiments (conducted in tandem with fellow psychologist Amos Tversky). The lessons from it are manifold and worth reflecting on today.

Take two hypothetical investment situations. One, your million-dollar portfolio to start the year ends it at $1,250,000, up 25%. Two, your million-dollar portfolio initially skyrockets to $1,500,000 by midyear for a 50% gain! But then negativity strikes and your portfolio ends the year at only $1,250,000—the exact same place as the first case.

If you are like me, you would rather have what’s behind door number one. Steady as she goes, please. It turns out, this is true of most people. And this behavioral quirk has very relevant investment implications beyond contrived hypotheticals. It is a type of bias—one that can steer you wrong. In my view, understanding this—and how your own mind can work against you—can make you a better investor.

So, what is going on in the example above? This phenomenon is myopic loss aversion, or prospect theory. Given the prospect of two equal payouts, people tend to favor the one that doesn’t involve any “loss.” The “myopic” part comes from the notion that you would only know you suffered a “loss” from checking your portfolio relatively frequently—portfolios one and two would be exactly the same if you just checked them at yearend.

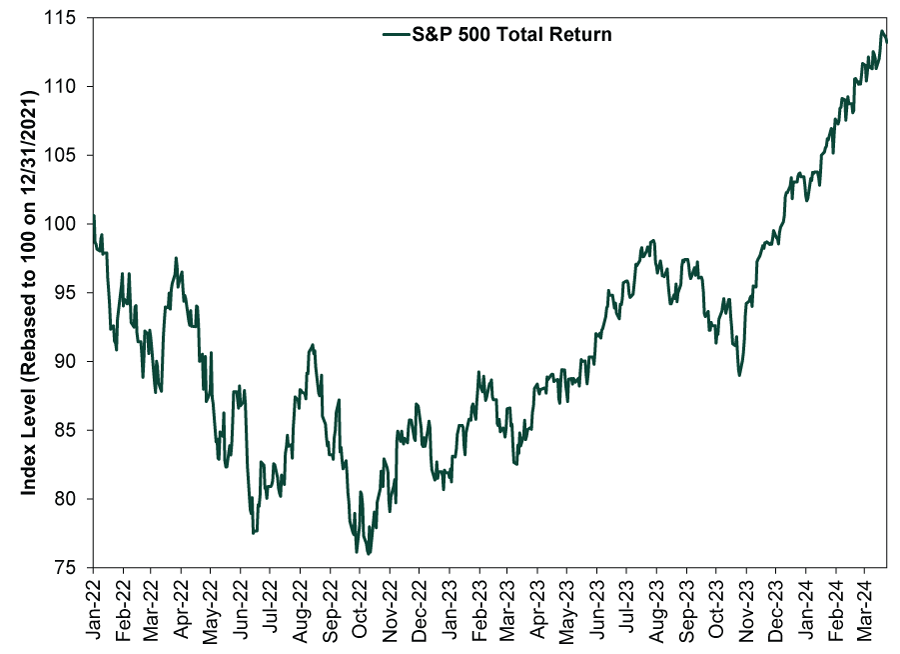

To see how this might apply in the real world, consider Exhibit 1, which more or less illustrates the point. Pretend you invested $100,000 in the S&P 500 at the end of 2021, then didn’t check on it until yesterday. Logging into your account after the market closed that day, you would see a 13.2% return including dividends.[i] Not too shabby, you might think. Up right around average! But then you dig a little deeper and see this stretch included a -24.5% decline from early-2022’s peak through that October 12.[ii] Prospect theory suggests many folks’ feelings would now shift.

Exhibit 1: This Wasn’t Hypothetical

Source: FactSet, as of 3/27/2024. S&P 500 total return, 12/31/2021 – 3/26/2024.

Now, the ideal scenario—and what we aim to do—is identify 2022’s bear market early enough to avoid part of it and get back in somewhere closer to the October low. But barring this, staying patient and steadfast is a critical skill—and one it can pay to hone because virtually every investment offering more than cash-like returns is going to have uncertain periods of negativity. Sometimes those will be bear markets. Sometimes they will be brief corrections that come and go without warning and are, in my view, not a call to action—like the autumn 2023 correction. There is, put simply, no strategy that can deliver growth and capital preservation in the true sense of those terms.

The difference with hypothetical scenarios—and retrospective snapshots—is that investing is ongoing and in real time. Being honest and introspective about how you reacted during past volatility is one way to get some insight. And I think studying similar situations—historical or simulated—offers important lessons for investors.

Now, here some may be tempted to conclude I am arguing for never (or rarely) checking your portfolio. Not so. I think the Ostrich Method is unrealistic, especially since big market moves make loads of headlines and common chatter. Keeping emotions in check is key, which is why the less obvious lesson is far more useful: You probably value losses differently than gains.

Kahneman and Tversky’s psychological experiments underlying prospect theory suggest people feel losses more than twice as much as equivalent gains. I think most people intuitively understand the pain of losing—the agony of defeat—outweighs the thrill of victory. Win a prize? Mission accomplished, celebrate, check it off the list and—out of mind. You move on to the next thing. Lose a prize? Crushing mental anguish and endless rehashing of would haves, should haves and could haves. The one that got away is what tends to stick in memory. I can still recall viscerally the own goal I “scored” in middle school soccer!

Recognizing your mind’s tendency to magnify negative outcomes’ impact—and taking that lesson to heart—opens the way for cool-headed rational thinking about your investments. Namely, volatility isn’t anything to shun. When the market—and your portfolio—gyrate wildly, the urge to get out can be overwhelming. But that can just be myopic loss aversion kicking in. The worst part: The cognitive bias can compel people to inadvertently take more risk just to avoid short-term volatility.

Being out of the market may let you stay clear of the emotional rollercoaster that comes with stocks’ swings. However, the imagined “safety” is illusory if this takes you further away from your long-term financial goals. And it presents a thorny question: When should you get back in? To keep loss avoidance from bending you out of shape, confront your emotional urges head on. Understanding how such aversion can affect your decision-making is a better solution than letting it rule you.

When negativity strikes, obsessing over short-term swings—and feeling motivated to act—can be very counterproductive. Rather than rashly sell stock, take stock. Or take a long walk—a much more useful exercise in more ways than one. Visit a friend. Go to a movie. Anything to separate yourself from the emotional stimulus for a while. Then, instead of a knee-jerk reaction to water under the bridge, I can carefully consider all the potential consequences of what—if any—action I might take in a fuller, forward-looking context.

Remind yourself who investing is for: future you. The name of the game is to steer your portfolio to meet your long-term goals. Volatility may strike fear, but that isn’t reason enough to make portfolio decisions with wide-ranging consequences. Think them through. Then decide. Are your actions more or less likely to make future you better off? Keep in mind high uncertainty—and big market swings—are normal. They are also the price you pay for stocks’ long-term gains.

In the heat of the moment, the impulse to avoid losses may seem “safe.” That is a trap, in my view, that can pull you from your goals. One of the biggest challenges any investor faces is staying focused on those long-term goals and needs when confronted with short-term setbacks and emotions that can put you off course. There is no perfect solution to this. But being mindful of it is a great start—in large part thanks to Kahneman who helped light the way.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.