Personal Wealth Management / Market Analysis

Sorting Through the Potential Shutdown Noise

Government shutdowns provide political drama, but aren’t likely to ding the economy or stocks.

Our discussion of politics and political issues is intentionally non-partisan. We assess these developments solely to share our view of their potential market impact (or lack thereof). We favor no political party nor any candidate.

Pity poor President Trump. All year, he has said he would like a good government shutdown to use as a negotiating tool. To date, no such luck. January’s barely lasted a weekend. February’s was a nine-hour overnighter, when most government offices are closed. Even now his threat to force a shutdown if Democratic leaders don’t fund a border wall wouldn’t be huge, impacting only the roughly 25% of government functions that aren’t already funded through September 2019. Perhaps that is why media chatter surrounding this potential shutdown is much more benign than past standoffs, with most commentary encouraging investors to brush it off rather than warning of economic or stock market pain. That tone seems apt to us. If no government shutdown has ever caused a recession or bear market, a partial-partial shutdown shouldn’t either.

Congress and the White House have been doing this latest shutdown dance since before midterms. To avoid the circus of a pre-vote shutdown over border-wall funding, lawmakers split the funding bill into three parts in September. Two of them, including funding for Defense, Labor, Health and Human Services, Energy and the Veterans Administration, passed easily, funding those departments through next September. That means nearly 75% of fiscal 2019’s funding is in place. But the border wall can-kick expired on December 10. Congress, not wanting to inject partisan rancor into President George H.W. Bush’s funeral proceedings, passed a two-week stopgap that punted the deadline to December 21, leaving the potential for about one-fourth of non-essential government operations to shut down without a new deal by then.

Normal government shutdowns like 2013’s are “partial” shutdowns because they close only non-essential (the government’s term) operations. Usually that includes National Parks, the Smithsonian, the SEC, national statistics agencies and other civil service. Animals at the National Zoo are fed (essential), but the gates are closed to visitors (non-essential). The Congressional Research Service estimated 2013’s shutdown furloughed “approximately 40% of the federal civilian workforce” or “roughly 850,000 employees.” This time, a shutdown would hit far fewer employees—potentially only 350,000 according to one source. National Parks and the Smithsonian are already funded, which could force journalists to find new pictures to accompany shutdown commentary—the traditional “Museum closed due to government shutdown” signs won’t be on display. Hence our tongue-in-cheek term, partial-partial shutdown.

Therefore, any potential shutdown would likely have even less market and economic impact than your run-of-the-mill closure. Which is … hardly any impact at all. As Exhibit 1 shows, returns during and after government shutdowns are far from disastrous.

Exhibit 1: US Stock Returns Surrounding Government Shutdowns

Source: Congressional Research Service and FactSet, as of 12/14/2018. *Before 1980, shutdowns were less complete, with some agencies staying open on the presumption Congress didn’t intend for them to close. Reinterpretation of the Antideficiency Act changed that.

While pre-shutdown nerves might ding sentiment and contribute to choppiness before a shutdown, the impact seems small and inconsistent. There seems to be even less impact on subsequent returns. Shutdowns in 1981 and 1990 occurred during unrelated bear markets. 2018’s shutdowns bookended a global stock market correction. But US spending battles weren’t exactly on investors’ list of concerns during this volatility, which centered on tariffs and rising interest rate fears.

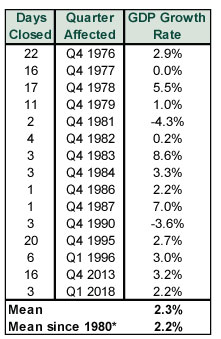

As Exhibit 2 shows, GDP growth is similarly resilient, with only two quarterly contractions in periods containing a shutdown (or multiple shutdowns).

Exhibit 2: GDP Growth in Quarters of Government Shutdowns

Source: Congressional Research Service and St. Louis Federal Reserve, as of 12/14/2018. Shutdowns were combined in some quarters to show total days closed. *Before 1980, shutdowns were less complete, with some agencies staying open on the presumption Congress didn’t intend for them to close. Reinterpretation of the Antideficiency Act changed that.

Here, too, the two contractions had more to do with pre-existing recessions. In each case, contraction began a quarter before the government shutdown began—before any conceivable impact could hit the economy. Even the 26-day government shutdown from late 1995 to early 1996 didn’t visibly knock growth.

The reason shutdowns pack little punch: They don’t cancel the associated economic activity—mostly, they just delay a small slice of it. A very small slice, considering non-defense Federal government spending was only 2.7% of full-year 2017 GDP.[i] Furloughed federal employees usually receive back pay when the new funding bill passes. Hence, shutdowns likely don’t erase their consumer spending—at most, they probably delay it. Some argue shutdowns have a cascading impact because furloughed employees don’t make their daily lunch or coffee runs, which dents sales at those businesses, which hurts their profits and employees, which limits those employees’ spending, lather, rinse, repeat. And sure, for those specific businesses, we imagine there is a short-lived pinch—much as our local eateries probably don’t get as much business on days your friendly MarketMinder editors don’t go to work. But extrapolating an economy-wide slowdown from a few slow days for some businesses in Washington, D.C. is a bridge too far. Besides, we are betting a not-inconsequential portion of those employees would redirect their consumption to leisure-oriented activities if they couldn’t work.

Mostly, we think this shutdown debate is interesting for what it shows about sentiment’s evolution during this bull market. Back in 2013, sentiment was black as the shutdown deadline neared. Today, the mood is overall calmer, even with the shutdown chatter coming amid a market correction. We think that speaks to a later-stage bull market—and the fact Americans have seen this movie before. More see correctly that a short-lived, partial-partial government shutdown—if it happens—just isn’t the doomsday scenario many thought before.

[i] Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, as of 12/14/2018. Non-defense Federal government spending as a percentage of GDP.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

See Our Investment Guides

The world of investing can seem like a giant maze. Fisher Investments has developed several informational and educational guides tackling a variety of investing topics.