Personal Wealth Management / Economics

Half Full or Half Empty?

Debt ceiling dramatics came to a conclusion Tuesday, leaving many frustrated in its wake. Here’s a look around the news at what’s poking that frustration—and largely unnoticed remedies.

Number 103

The House of Representatives and Senate have both now passed the debt limit increase bill. This may have surprised some, but not us—as we expected, the 103rd increase in the debt ceiling’s 94-year history passed both houses of Congress and has been signed by President Obama, lifting the debt ceiling. While many in the press have suggested this debate was unusually heated, the fact is it played out nearly exactly as past debt limit debates. Amity Shlaes and John Thorndike included an illuminating anecdote from the annals of debt ceiling debate history in their piece Sunday. And in our recent piece, “Full Faith and Credit,” we gave three timelines as examples of how these debates have unfolded in the more recent past. We could have given many, many more.

There will be more debt ceiling debates in the future. Just keep this as a reminder to take media coverage that doesn’t take politicians’ statements about default, doom-and-gloom and deadlines with many grains of salt.

But It’s a Bad Deal

Now that there’s a deal, some opine it isn’t a good thing—we’re either not going to appease ratings agencies (why we’d want to or how we’d actually appease these confused analysts is beyond us) or it’s going to hurt the economy somehow. Beyond the raters (whom we address here), the reality is the new debt ceiling deal has almost no economic impact. A higher ceiling? Meaningless. Not enough cuts? We might agree, but that’s not crisis-inducing, especially considering how cheap our interest rates currently are. Too much in cuts? Well, some in the more-government-spending crowd have argued for two years that 2009’s $787 billion stimulus was too small. If that’s too small to have an impact, we wonder exactly how “cuts” (which are really more like a slower rate of spending) averaging less than $150 billion a year (and are almost non-existent up front) are big enough to have a dire impact. That doesn’t seem like a recipe for a 1937 redux to us (especially considering 1937 wasn’t all about spending cuts).

“Zombie” Consumers Save More Money

June US consumer spending fell -0.2%, missing estimates for slight growth. Personal incomes, meanwhile, rose—pushing the strangely calculated savings rate higher.

Some have recently suggested the US consumer is overleveraged and therefore is unable to drive recovery. And we’re sure some will find confirmation in Tuesday’s spending data. But let’s check the theory. First, consumer spending (like all economic data) frequently fluctuates. Consumer spending has fallen multiple times, like points in 2003 and 2005—and that didn’t presage recession. Expectations widely continue to be for ongoing growth this year—and we agree. Seeing economic data that miss expectations—even decline for a month—is just normal.

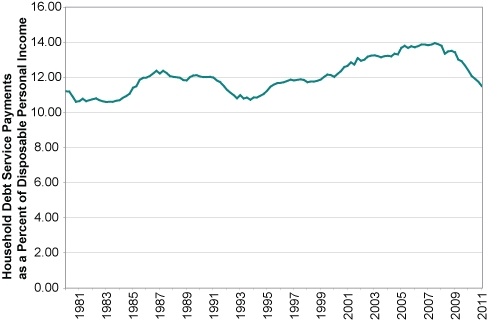

As for arguments US consumers are overleveraged, that usually hinges on comparisons of total debt outstanding to income. Which can be a faulty comparison. For example, you don’t have to pay off your mortgage in a given month or year. Rather, your income must be sufficient to service it. So the comparison should be income to debt-servicing costs—and that’s shown in Exhibit 1:

Exhibit 1: US Household Debt Service Payments as a Percent of Disposable Personal Income

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Looks like debt service to income has been falling recently. It may make a good headline, but it doesn’t look like consumers are increasingly overleveraged to us.

Moreover, if you fear consumers are overleveraged, then a report like today’s should be encouraging. Disposable incomes rose and consumers spent less—which makes them more liquid.

It’s Not All Government

Over in the UK, the punditry commonly bemoans the nation’s slow rate of growth—much as they do in the US. But beyond that point, there are some stark differences. Britain passed austerity measures in 2010 and has attempted to follow through—with a higher VAT tax, spending cuts, lower corporate tax rates and more. In the US, we’ve largely pursued a program of greater federal government spending. Yet growth rates are eerily similar—which should tell you there’s much more to what determines an economic growth rate than government policy. Just consider that point when you hear the competing arguments for either greater government spending or more austerity, both ostensibly to foster growth.

It’s Not All the Fed, Either

Amid the debt ceiling debate, an odd thing happened: Treasury rates fell. We’ve already discussed the fact this should have called into question the theory that the debt ceiling was such a problem, but beyond that there’s something else: QE2 ended a month ago and rates are down. So much for the theory the Fed was solely keeping rates low.

The Tug of War, Illustrated

It seems to us today’s debate over matters both economic and political (like the debt ceiling) are pure examples of the bifurcated sentiment we’ve written about this year. And they don’t stop with the discussions above—just consider China, who some fear will overtake the US as the world’s largest economy, while others simultaneously fear China tightening too much and tanking its economy. Or blaming corporations for boosting profitability while not hiring much. There’s fodder in each for bulls and bears alike.

Ultimately, a balanced, apolitical point of view is needed to see markets and the economy clearly. Otherwise, you’re likely to interpret any piece of data in line with your bias—and be highly disappointed by the outcome of every political debate. (After all, politicians often promise a lot and deliver very little.) A clear view shows solid global economic growth and US economic growth that isn’t torrid presently but has recouped nearly all of the output lost in the recession. Corporations are flush with cash generated by rising revenues, productivity and earnings. Stocks have roughly doubled since the beginning of the bull market. And there’s likely far more fuel in the tank for continued growth beyond what we see as a year of rotation within a broader bull market.

Feeling frustrated by political bickering in Washington is perfectly understandable (and believe us, we share that angst). Good thing we don’t have to rely on them economically. When you look up from the debt debate (in its many forms) and the primary worries of the day, the innovation and dynamism of capitalism become easier to see. Don’t believe us? Buried beneath all of Tuesday’s headlines was this story of industrial rebirth in what many still see as America’s “rust belt.” And that dynamism is the antidote to a frustrating Washington that’s utterly disconnected from Wall Street, Main Street and every street in between.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.