Personal Wealth Management /

The Tale of the Dollar’s Demise

Has the dollar lost its status as the world’s reserve currency?

How long before China’s yuan encroaches on the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency? Photo by China Photos/Getty Images.

It’s Halloween, folks! Time for costumes, trick-or-treating, Charlie Brown and—of course—ghost stories. So wouldn’t you know one of the biggest ghost stories in global markets has made a comeback this Halloween season: dread of the dollar’s impending demise. Near annually, it seems folks fear the dollar is on the verge of losing its status as the world’s preferred reserve currency, with economic decline and poor equity returns to follow. As with most ghost stories, however, reality is far more benign.

When people refer to the dollar as a reserve currency, they generally refer to one of two things: the dollar’s high weighting in other countries’ foreign exchange (forex) reserves or its wide use as an intermediary in foreign transactions. Let’s start with the latter—it’s simpler. Some currencies aren’t directly convertible to each other—China’s yuan, for example, has historically converted only to US dollars, Japanese yen and Australian dollars (though the country recently signed swap agreements with the eurozone, UK and Russia). So if a Chinese steel manufacturer sells to a Polish firm, the Polish firm converts its zlotys to dollars to buy the steel, and the manufacturer presumably converts its dollars to yuan.

As you can imagine, it’s sort of a hassle—an extra hurdle to international commerce. The US doesn’t really gain anything from being an intermediary—the Treasury and/or Fed don’t get a brokerage fee. It has no bearing on Treasury rates. It’s just a thing that happens and makes foreign trade that much harder. If more currencies were directly convertible to each other—if the dollar or euro didn’t account for 74% of all payments—global trade would be freer and, likely, higher. This would be good for the US and global economies and stocks! Higher and freer trade means higher potential earnings. Stocks love it.

The forex reserve issue is a bit more complex. Each country keeps a stockpile of foreign assets—mostly sovereign debt and some cash—to use as a buffer for their own currency. Ostensibly, it’s to deter and defend against speculative attacks. Imagine you run the central bank of your own country, Youdonia, and your currency is the youdo. If so-called speculators drove down the value of the youdo, you could use the assets in your forex reserves to buy up the youdo to lift the exchange rate back up. Conversely, if the youdo got too strong, making your exports significantly less competitive, you could use your spare youdo stockpiles to buy up more foreign assets, driving the youdo back down and beefing up your forex reserves for a rainy day.

These days, most countries keep pretty big forex buffers—the world total is just shy of $11 trillion, according to the IMF. Of that amount, $4.9 trillion is considered “unallocated”—countries don’t report the breakdown to the IMF. The remaining amount, about $6.1 trillion, is conserved “allocated” reserves and reported to the IMF’s Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER).

All of this is to say there is a huge forex reserve pool, and in order to fill it out, countries need very liquid, easily convertible assets from very deep markets. Few assets fit the bill, and the dollar is most qualified—there are over $16 trillion in US Treasurys outstanding. It’s the biggest market by far, the most liquid and the most convertible. Hence why the dollar currently accounts for 61% of all allocated forex reserves.

But wait! In 1999, the dollar accounted for 71%! What happened?

In short, the euro. When it came on the scene, countries converted their reserve holdings of French francs, German marks, other national currencies and the European Currency Unit to euros, and these euros accounted for about 18% of all reserve holdings. Over time, as the euro became more viable, countries gained more confidence in it as a reserve asset, and they increased their holdings. Today, the euro accounts for about 24% of all allocated reserves.

So the US dollar is already losing global market share. That “dethroning” people fear so deeply started over a decade ago. And it likely keeps happening, slowly, over time—as global money supply and economies grow, the world needs larger reserve piles. As more currencies grow up, it’s just natural countries will allocate new reserves in a more diversified manner. Perhaps, in 50 years, instead of having 61% in dollars, 24% in euros, 4% in sterling and the rest in the yen, Swiss franc, Aussie dollars and everything else, they’ll have 40% in dollars, 30% in euros, 20% in Chinese yuan, 5% in sterling and the rest in whatever. Diversification is a perfectly rational, globally productive move—it means global capital markets are ever deeper and more liquid. Just what global investors should want!

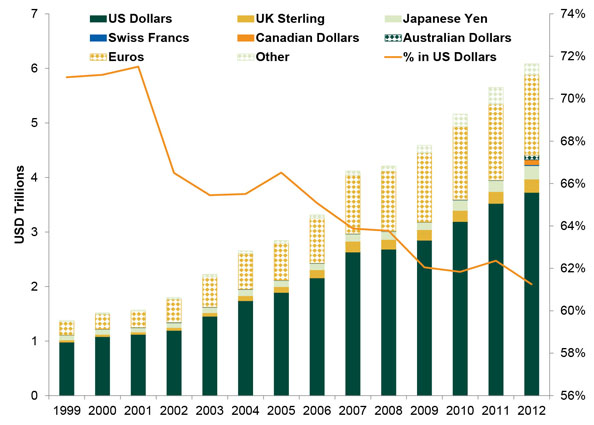

But here’s the thing: This doesn’t mean demand for US assets tanks. It simply means the dollar has a smaller slice of a much bigger pie. That’s exactly where it stands today versus 14 years ago—and over that time, dollar holdings have nearly quadrupled. (Exhibit 1) Yes, you read that right! The dollar is more in demand than ever before, even with the heightened competition.

Exhibit 1: Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves

Source: International Monetary Fund, as of 10/30/2013.

Could something happen in the future to reduce dollar demand? It’s possible, sure, but evidence suggests it would take something utterly gigantic and unprecedented. 2011’s heated debt ceiling debate and S&P’s US credit rating downgrade didn’t do it. Foreign demand for Treasurys remained firm throughout the latest budget bickering. Big bear markets and recessions in 2000 and 2008 didn’t kill global greenback hunger. And if it’s rising debt you fear, consider that Japan’s gross public debt is about 220% of GDP—and international yen holdings are rising, not falling.

Then, too, there would have to be a viable alternative—right now, there isn’t a replacement. UK gilts are liquid and stable, but the market isn’t anywhere near as big as that of US Treasurys. Together, eurozone debt markets are bigger, but recent events (i.e., the debt crisis) show they’re nowhere near stable enough for now. The Japanese government’s recent and occasional currency meddling makes the yen less attractive. And China’s yuan has years, if not decades, of liberalization before it’s anywhere near ready for prime time.

So don’t let this age-old ghost story haunt your portfolio! The dollar’s “demise” simply isn't the threat some make it out to be. There is no reason stocks and the US economy can't continue climbing over time as the dollar gets more competition in the forex reserve arena.

If you would like to contact the editors responsible for this article, please message MarketMinder directly.

*The content contained in this article represents only the opinions and viewpoints of the Fisher Investments editorial staff.

Get a weekly roundup of our market insights

Sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter.

You Imagine Your Future. We Help You Get There.

Are you ready to start your journey to a better financial future?

Where Might the Market Go Next?

Confidently tackle the market’s ups and downs with independent research and analysis that tells you where we think stocks are headed—and why.